Training for a half marathon can be challenging. Sticking to a training plan can be difficult, especially if you don’t know where to start. We will break down the various types of workouts, programming, and nutrition. Once you understand the principles, committing to training will be much easier.

Long Run

Purpose: (2,5,8)

- Long-slow runs can improve your running economy which is the ability to run at the same pace with less energy. This happens because we become more efficient as we adapt to running. Additionally, these runs are fundamental to building a solid aerobic base or VO2 Max. Slowing the pace and increasing the distance allows you to acclimate to longer distances.

Intensity:

- These runs should be performed using a speaking pace. This means you run at a pace that you could hold a conversation with a training partner without feeling out of breath. These runs are not meant to be overly fatiguing, so when in doubt, run slower.

- Performed at 60%-80% VO2 Max or Heart Rate Reserve (2,8).

- Performed between 74-81% maximum heart rate (MHR) (8).

Duration:

- The duration will incrementally increase around the distance of your race at the end of the program.

- My long runs began at 3 miles and I added one extra mile each week until I was comfortable with 10-12 miles before race day.

Frequency:

- Long runs are generally one to three days per week. This program includes one shorter and one longer easy run.

Progression:

- An increase of one mile per week is how long runs are typically progressed. For newer runners, quarter or half-mile increases may be used.

- Intensity, duration, and frequency should not increase more than 10% each week to facilitate recovery and reduce injury risk. (8)

Pace/Threshold Run

Purpose:

- Threshold training allows you to become comfortable with your race pace. These runs improve running economy, lactate threshold, and VO2 Max (8).

Intensity:

- Run at or slightly above your goal pace. Alternatively, 85% of your maximum heart rate may be used (8).

Duration:

- Aim to hold lactate threshold or race pace for 20-30 minutes (8). You also have the option to break up the duration into intervals.

Frequency:

- Pace runs can be performed 1-2 days per week (2,8).

Progression:

- When 30 minutes at race pace feels easy, progress by adding time and not intensity.

Interval Training

Purpose:

- Interval training plays an important part in performance on race day. Intervals help with the “kick” that athletes use to run faster for longer.

- Intervals improve VO2 Max, lactate threshold, and exercise economy (8).

Intensity:

- Close to or exceeding VO2 max (85-115% of VO2 Max).

- As you become more conditioned, a higher training percentage of vo2 max is required to progress.

Duration:

- Work duration can be 30 seconds to five minutes.

- The work-to-rest ratio is typically 1:1.

Frequency:

- 1-2 days per week.

- Intervals should be used sparingly to prevent overfatigue, especially in newer runners to reduce the risk of injury.

Interval Training Workouts

Track Repeats:

- Duration: 3-5 minutes work, 1:1 work: rest ratio.

- 400-1200 Meters for 4-8 reps

- Intensity: 85-90%+ VO2 Max

- Tips: Focus on arm swings, leg drive, and increasing step rate. Do not focus on increasing step length. Aim for the shortest possible foot contact with the ground.

Hill Sprints:

- Duration: 30-second to 3-minutes work for 4-12 sets

- Intensity: 85-90% vo2 Max. You can change the intensity with the grade of the hill.

- Tip: Driving up the hill with fast powerful steps and drive your arms.

Fartlek (Speed-Play):

- Duration: 20-60 minutes of jogging and sprinting intervals.

- Intensity: Easy run at 70% VO2 Max with hill or wind sprint intervals for fast bursts (30-60 sec) of running at 85-90% VO2 Max.

- Tips: Lock onto a target such as a tree sprint to it for 30 seconds, and then slow back down to a recovery pace for 5 minutes. Repeat for 2-6 miles.

High-Intensity Interval Training (HIIT)

- Intensity: Greater than VO2 Max 100%+.

- Duration: 30 seconds-3 minutes work with a 1:1-1:6 work: rest ratio (2).

- Tips: HIIT training can take the form of many different workouts such as burpees, hill sprints, jump squats, or even jump rope.

Cross Training

- Weightlifting, swimming, and cycling can add movement variety to your training. This can help reduce boredom and prevent overuse injury by spreading out fatigue to other muscles and joints. I substitute an easy run with a 60-minute ride on the bike.

- Resistance training has been shown to improve running efficiency and performance in endurance athletes (5). Strength training can also reduce injury risk by creating shock-absorbing muscles to protect the ankle, knee, and hip. Aim for 2-5 resistance training days a week with 2-3 sets of 5-12 reps per exercise. Look here for more information on resistance training.

- Resistance exercise can include a variety of movements such as bodyweight calisthenics, barbells, machines, deadlifts, step-ups, and pull-ups. Runners should pay special attention to developing their leg strength and power.

- For example, 3 sets of 10 repetitions of lunges will improve the strength of the quads, and glutes, and stabilize the core muscles of a runner.

Programming

The program’s length depends on each runner’s training history. A beginner may take longer to build up to 13.1 miles. With some experience, 3-6 months would be a reasonable timeline for a half marathon prep. Keep in mind that aerobic adaptations can take a long time. For instance, improving aerobic capacity by 10-30% can take 2-5 months (6). A running frequency between 3-5 days a week is a sweet spot because more may cause overtraining and less than that may be too little stimulus (7).

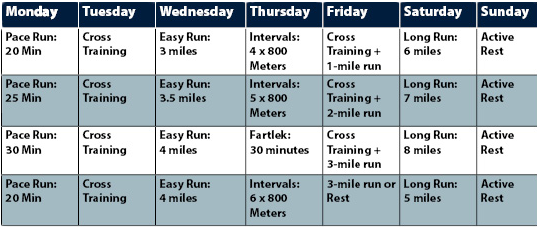

Preparatory Phase (4 weeks – 36 weeks)

The goal of this phase is to build an aerobic base using a lower starting intensity and volume that increases throughout the phase. Adding 8 weeks in the preparatory phase may be wise to work on a weakness. For instance, a deconditioned adult may begin with a walk-jog program with 15-25 minute runs and 15-90 minute walks along with a resistance training program.

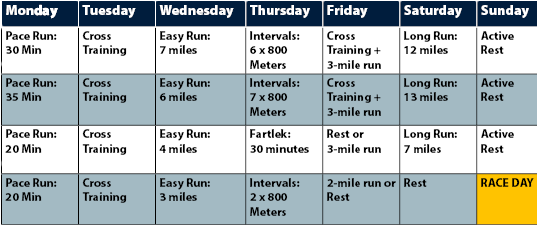

Specific preparatory

This phase aims to improve technique, endurance, and speed. These goals require a shift towards interval and threshold training. Workouts increase in volume and intensity each week to build capacity. A taper is placed 7-28 days before race day by cutting the volume of the workouts. Tapers have been shown to improve performance on race day (2).

Race Day

- Sleep 7-9 hours the day before.

- Eat a correctly sized pregame meal depending on how much time before the starting time.

- Get there early and dynamically warm up.

- The goal should be to hold a pace consistent with your pace runs.

- Bring nutrition and hydration with you!

- You earned it! Now is the time to show all of your hard work!

Nutrition

Calories

- Depending on your weight, sex, and speed, running can burn 100s of calories every hour of training. It is important to not forget to fuel your body with energy to maximize performance.

- To find out how many calories you burn while running here is a simple equation

- Running Modifiers (10)

- Multiply by pounds and minutes to find kcal. These factors are in units, (kcal x lb^-1 x min^-1).

- 5 mph: .061

- 6 mph: .074

- 7.5 mph: .094

- 9 mph: .103

- 10 mph: .114

- Example: 250 pounds x 60 minutes at 6mph (.074) = 1,110 kcal

- Running Modifiers (10)

- Look here for more information on calories

Carbohydrate

- A higher carbohydrate diet can improve endurance performance compared to a high protein and fat diet (9). This is because depleting glycogen stores, the carbs in your muscle, has been linked to fatigue. Carbohydrate intake before, during, and after exercise optimizes glycogen in the muscle.

- The general recommendation for athletes:

- 5-10 g/kg (6). The exact number depends on the athlete’s sex, size, and activity level.

- Carbohydrates can comprise 55-70% of the total caloric intake.

- 1 hour or less:

- 5-7 g/kg/day (9).

- 1-3 hours of training:

- 6-10 g/kg

- 4 hours or more

- 10-12 g/kg

- Carbohydrates should be consumed at a rate of 30-90 grams per hour in events lasting longer than 1 hour (6,8).

- Select whole food sources of carbohydrates such as oatmeal, sweet potatoes, and honey, instead of processed foods like candy and ice cream.

Carbohydrate loading (8)

- Consumption of 8-10g/kg of carbohydrate 72 hours before, and 10-12 g/kg 36-48 hours before may improve race performance. The idea is that by eating more carbohydrates, your muscles will store more glycogen that you can use for energy during the race. Practice this technique before a long run and dial in what types of carbs work best for your digestion. Personally, my rice cooker was an extremely useful tool to get in enough carbohydrates.

Protein

- Ranges from 10-35% of total energy intake.

- Endurance athletes should consume 1.2-2 grams per kilogram of body weight (9).

- If the athlete is in a caloric deficit, they may require more protein to prevent muscle loss.

Fat

- Endurance athletes are recommended to eat 20-25% fat (6).

- Some athletes choose to adapt their bodies to burn fat as fuel “butter burners”. Personally, because of the tight relationship with carbohydrates and glycogen, I choose to use carbohydrates as my primary source of running fuel.

Caffeine

- Consumption of 5 mg/kg of caffeine can increase the length of time you can exercise before exhaustion (5).

Precompetition Meals

- 1 or fewer hours

- .5 g/kg of carbohydrate

- Example: Coffee sweetened with honey and a banana.

- 2 hours before (8)

- 1 g/kg carbohydrate

- Toast, eggs, fruit, and coffee

- 4 hours before (8)

- 1-4 g/kg of carbohydrate

- 0.15-0.25 g/kg protein

- Breakfast burrito with fruit

- After an intense race, glycogen stores can be restored rapidly with carbohydrate meals every 15-60 minutes (8).

Hydration

- Drink 5-12 oz of water every 15-20 minutes of exercise if the activity is less than an hour.

- If you are running over one hour, a sugar and electrolyte drink with a 5-10% carbohydrate solution can improve performance and promote hydration. (6,8)

- Drinking fluid is important to prevent loss of more than 2% of mass, which would suggest dehydration.

Recovery

- Keep slowly moving after the race to gradually lower your heart rate.

- Static stretching of your legs may reduce soreness.

- Refuel with plenty of fluids, carbohydrates, and protein.

- Check your feet for blisters.

Running Form:

- To improve running economy, run with a shorter stride length but faster frequency (8).

- Do not bounce up and down. If you notice your head bobbing noticeably, you have room for improvement. This is because if you use energy going up and down, that is wasted momentum that could be used to propel you forward.

- Relax your shoulders and neck. Excessive tension is inefficient and can make fluid mechanics hard to achieve.

Definitions

Running economy:

The amount of energy you burn to run. With practice, running becomes more efficient as your brain more smoothly controls muscle activation and your form improves. With a higher running economy, you will use less energy to run at the same speed (5).

Aerobic Base / VO2 max:

The consumption of oxygen is the primary measure of aerobic endurance. This is because oxygen is used to create energy to sustain aerobic exercise. The maximum amount of oxygen in ml you can produce each minute per kilogram is your VO2 Max ml/kg/min. At rest sitting quietly, one MET is equivalent to 3.5 ml/kg/min (5). Aerobic base can be improved with long runs, intervals, and pace training.

Anaerobic Threshold/Lactate Threshold:

At higher intensities, lactate is produced at a faster rate. The intensity at which lactate builds up rapidly in the blood levels faster than it can be cleared is called the lactate threshold (5). Buffering lactate can be improved with interval and pace training.

Heart Rate Reserve (HRR)

- Heart rate reserve is the difference between your maximum and resting heart rate.

- Maximum Heart Rate – Resting Heart Rate = Heart Rate Reserve

- ACSM guidelines(4):

- Light: 30-39% HRR

- Moderate: 40-59% of HRR

- Vigorous: 60-89% of HRR

Target Heart Rate (THR)

- Target Heart Rate = Resting Heart Rate + ((Heart Rate Reserve) x % range)

- Ex: A 23-year-old with a resting heart rate of 40 at a target of 65-85% intensity

- (152 X .65) + 40= ~ 139

- (152 X .85) + 40= ~ 169

Considerations:

- Many runners believe that if some is good, more must be better. While this is true for some, endurance athletes regularly train over 140 miles each week (1,5). These elites make careers out of building their aerobic base, bone density, and muscle often taking years to progress. Improper progression can cause overtraining and resulting injury. This happens because our body is damaged during training and requires recovery.

- Interval training can be swapped for any other interval workout. For instance, hill sprints could substitute for fartlek training on Thursday.

- Keep your long easy runs at a speaking pace.

- Don’t feel discouraged if you did not make a goal pace, or if you’re not progressing at a particular speed. Endurance training is difficult and it may take longer than anticipated to safely attain the results you are looking for.

Disclaimer: There is no “one size fits all” program because an individual’s conditioning, training history, age, health status, BMI, and sex, may require professional consideration. This program is not prescriptive and should be used for educational purposes only.

MY KEY LINKS:

- 💡 YouTube – https://www.youtube.com/@cartergansky

- 📸 Instagram – https://www.instagram.com/carter.r.gansky/

- 🐦 Twitter – https://twitter.com/CarterGansky

- 🌲 Linktree – https://linktr.ee/cartergansky

- 🔊 Discord – https://discord.gg/sQxvHH78Ga

WHO AM I:

I’m Carter Gansky, a fitness and health advocate and a Doctor of Physical Therapy in training. I explore the strategies and tools that help us live motivating, healthier, and more fulfilling lives.

GET IN TOUCH:

🧠 contactcartergansky@gmail.com

For collaborations or other business inquiries.

References:

- Billat, V., Lepretre, P.-M., Heugas, A.-M., Laurence, M.-H., Salim, D., & Koralsztein, J. P. (2003). Training and Bioenergetic Characteristics in Elite Male and Female Kenyan Runners. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, 35(2), 297. https://doi.org/10.1249/01.MSS.0000053556.59992.A9

- Ratamess, N. A. (2012). ACSM’s foundations of strength training and conditioning. Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

- Seiler, S., & Tønnessen, E. (2009). Intervals, Thresholds, and Long Slow Distance: The Role of Intensity and Duration in Endurance Training. SPORTSCIENCE · Sportsci.Org, 13, 32–53.

- Casado, A., González-Mohíno, F., González-Ravé, J. M., & Foster, C. (2022). Training Periodization, Methods, Intensity Distribution, and Volume in Highly Trained and Elite Distance Runners: A Systematic Review. International Journal of Sports Physiology and Performance, 17(6), 820–833. https://doi.org/10.1123/ijspp.2021-0435

- Chandler, T. J., & Brown, L. E. (Eds.). (2019). Conditioning for strength and human performance (Third edition). Routledge.

- O’Connor, F. G., Casa, D. J., Davis, B. A., St. Pierre, P., Sallis, R. E., & Wilder, R. P. (Eds.). (2013). ACSM’s sports medicine: A comprehensive review. Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

- American College of Sports Medicine, Riebe, D., Ehrman, J. K., Liguori, G., & Magal, M. (Eds.). (2018). ACSM’s guidelines for exercise testing and prescription (Tenth edition). Wolters Kluwer.

- Haff, G., Triplett, N. T., & National Strength & Conditioning Association (U.S.) (Eds.). (2016). Essentials of strength training and conditioning (Fourth edition). Human Kinetics.

- Whitney, E. N., & Rolfes, S. R. (2022). Understanding nutrition (Sixteenth edition). Cengage.

- Rolfes, S. R., Pinna, K., & Whitney, E. N. (2012). Understanding normal and clinical nutrition (9th ed). Wadsworth/Cengage Learning.